Community Building

The last Sunday in March is National Neighbour Day. Do you see a role for your verge garden as a bumping place to help create stronger neighbourhoods?

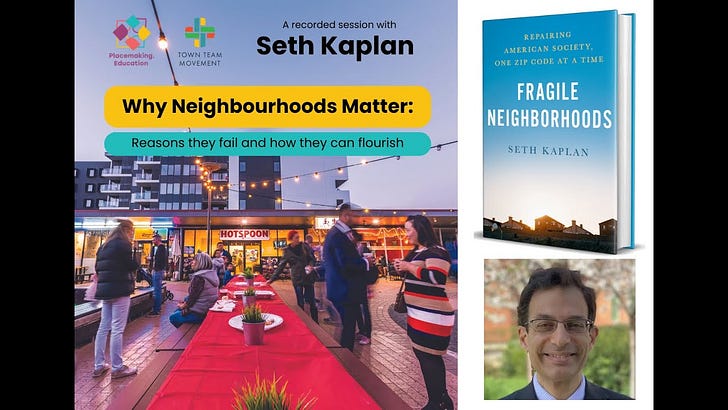

Below is a recording of the “Why Neighbourhoods Matter Webinar” with Seth Kaplan organised by the Town Team Movement.

I’ve been reading the book Fragile Neighbourhoods and it ties in with the aims and practices of the Shady Lanes Project. Although the book discusses American neighbourhoods, our countries share many of the same challenges.

Third Spaces

Within thriving communities, we have places where we meet our friends and neighbours. These are called third places - between private homes and work.

Third places include libraries, community centres, sports clubs, churches, local cafes, parks, and community gardens.

Perhaps, the richer and more varied our third spaces are, the less we need large private homes and gardens that provide for our needs: media rooms, entertainment rooms, playrooms, backyards, and so on.

While most groups and organisations who manage these third places pride themselves on being inclusive, the flip-side of that inclusivity is that they are also exclusive. The stronger the sense of belonging, the stronger the exclusivity. You must share the interest or faith, have money to attend, know the rules of the game, and generally fit in.

Clubs, churches, and community gardens are good examples of strongly inclusive community groups. They are part of a tapestry that makes up social fabric with strong hubs and enough connecting pieces to hold it together. At its extreme, it can be cliquey and tribal, but as long as there are plenty of options and no one group has undue dominance, that is not too much of a problem. If you don’t like one club, you try another until you find one that suits you.

These are comfortable places, at least for the insiders. They are stable and predictable. They lend themselves to professional placemaking and associated funding.

Edge Spaces and Bumping Places

Edge spaces are more varied and changeable. These include the streets and pathways between destinations. This is where we encounter people from different backgrounds, different classes, and different cultures. There is no common purpose or activity to connect us. There is no illusion of like minds. Outside hierarchies and status don’t count. It takes effort to listen, understand, and communicate.

That uncertainty breeds opportunities for change and innovation. Edge spaces are where you encounter new ideas, form new relationships, and make new friends.

When you use public transport, you are in an edge space. Some people prefer to avoid that discomfort by travelling by private car in their own private bubble insulated from the people and places outside.

The verge (nature strip, footpath, berm, tree garden) is the edge space we walk through. The anger generated in verge disputes shows how contested the space is. Maintaining the status quo of flat grass in this ignored space is the way to avoid disputes.

The Campaign to End Loneliness article, Tackling Loneliness through the Built Environment, discusses the role that the design of our neighbourhoods plays in tackling loneliness and helping people connect.

They differentiate between third places where strong ties are made with structured interactions (rules and norms so you know what to expect) and informal edge or bumping places.

Verge gardens, public yet connected to a residence, transform the anonymous space in front of our homes into a “bumping place” that encourages casual interactions.

It’s these everyday casual encounters as part of daily life that allow us to build relationships, starting from recognising a familiar face, then a nod, a greeting, a chat, and so on.

That is very different to community gardens, which provide a place for members to build deeper relationships with more inclusivity and corresponding exclusivity.

Verges have a much lower and broader version of inclusivity. Everyone has the legal right to walk down the street; and as verge gardeners, we must also consider people we don’t know and might never meet. Pedestrians, the postie, delivery workers, service providers, car drivers. Current residents and future residents. Different ages, different cultures, different purposes.

Verges are also home to the street trees that entire communities need for shade to help tackle urban heat and reduce skin cancer.

But wait! some will say. We grow food, share with neighbours, and build communities on the verge. Our kids have a playground. They either don’t see or don’t care about who or what they are excluding.

That wider version of low-key inclusivity and associated minimal exclusivity is enforced by council policies. We explain that more in our Understanding the Space articles.

The characteristics of place set the scene and shape conversations. Footpaths provide the connections between bigger places where people congregate in their inclusive niches. They are where we bump into people as we go about our daily lives.

It’s these everyday casual encounters that initiate and nurture relationships, starting from recognising a familiar face, then progressing to a nod, to a greeting, to a chat, and so on.

What sort of conversations have you had in bumping spaces? Have you noticed a difference if you are in a shady street with verge gardens, on a bare street, at the park?

The last Sunday in March is National Neighbour Day.

Do you see a role for your verge garden as a bumping place to help create stronger neighbourhoods? Could your community group use a verge garden project to increase the impact of your group? Upgrading to a paid subscription will give you access to more resources and discussion on managing localised projects.